![View the profile of [B^S] Molzahn Profile](https://lhcathome.cern.ch/lhcathome/img/head_20.png) [B^S] Molzahn [B^S] Molzahn

Send message

Joined: 21 Jan 06

Posts: 46

Credit: 174,756

RAC: 0

|

Hey again,

I hate to reply to my own post, and to detract attention from the "Good Luck Chrulle" post, but i found that the link provided gives you a signup form.

(Only through a direct search on Google using the words "Large Hadron Collider Forbes" will you get a link that will not give you a signup form; it's free but a hassle.)

So i will copy paste the article (sadly you will not see the wonderful images in the magazine):

Forbes Magazine, "Big Bang" by Daniel Lyons, 03.27.06

It will be the world's largest machine. It could explain the origins of the universe. But first a team of engineers has the gargantuan logistic challenge of putting the Large Hadron Collider together

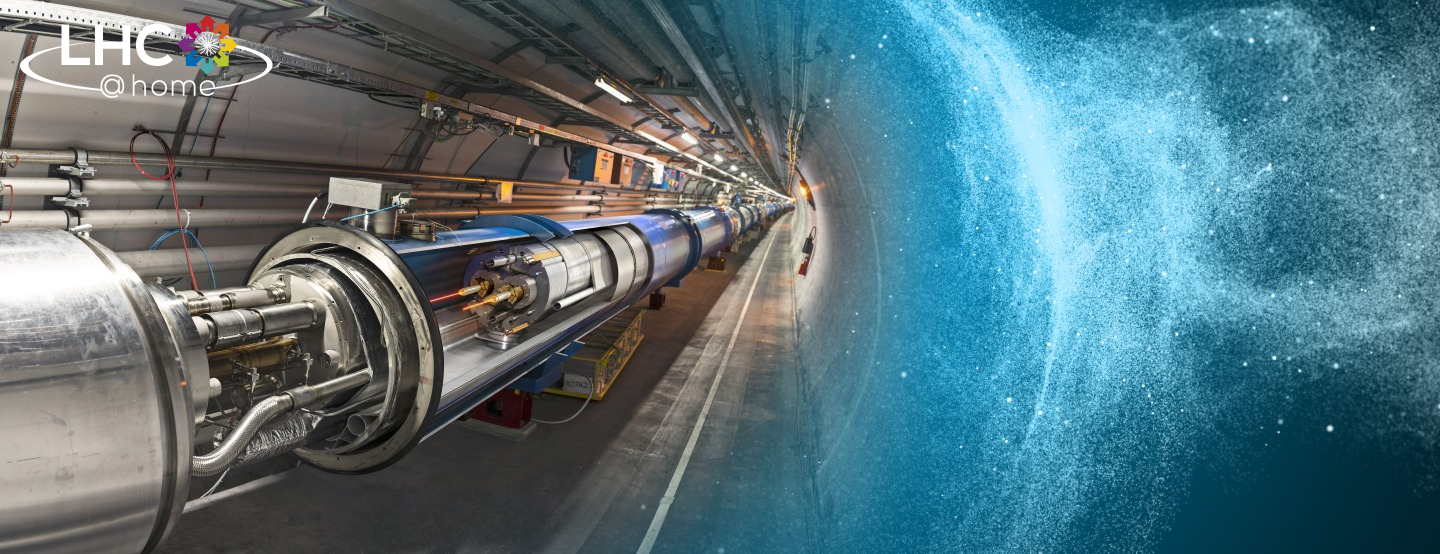

For physicists the large Hadron Collider will be the ultimate blackboard. This particle accelerator will have 1,700 enormous superconducting magnets stretched along a 17-mile-long underground tunnel spanning the French-Swiss border. The magnets, weighing up to 37 tons each, will accelerate two beams of protons in opposite directions to nearly the speed of light. These protons will collide in four giant particle detectors, the largest of which will occupy an underground cavern as big as Notre Dame Cathedral, producing a spray of particles that scientists hope will unlock profound secrets about the origins of the universe and the nature of matter itself.

The physics is difficult. The engineering is next to impossible. CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva, is faced with the dauntingly complex logistical assignment of first assembling an underground laboratory, which, despite its colossal scale, must operate with the precision of a Swiss watch, and next keeping it running without breakdowns. The resulting object, which has consumed more than a decade in the design and construction, will be the biggest supercollider in the world and the largest machine of any kind, containing 1 million components and carrying a price tag of $8 billion. The beast will run at a temperature just above absolute zero, making it colder than outer space. The complicated cryogenic system has already suffered a breakdown that delayed construction by six months.

"The challenge is enormous," says Pedro Martel, 39, an engineer who joined CERN in 1995 and leads a pack of software developers writing code that tracks almost every piece of the supercollider and schedules every step in its assembly. "We know there will be growing pains. Such a machine has never been built before."

CERN, founded in 1954, is funded by 20 European nations and is best known as the place where 15 years ago a British researcher named Tim J. Berners-Lee invented a way of sharing information over the Internet called the World Wide Web (otcbb: WWWB.OB - news - people ). These days CERN crews are racing to meet a summer 2007 deadline for the start of operations. In a vast hangar near CERN's 1,500-acre campus at the foot of the Jura Mountains workmen from France, Poland and a dozen other countries are building the 13,000-ton Compact Muon Solenoid detector, climbing scaffolding and blasting away with welding machines whose fumes fill the air. The detector is being built in 13 pieces, the largest of which weighs 2,000 tons. Each piece is lowered by a crane down a 300-foot shaft with such care that a single descent takes 24 hours. Some sections will have only 20 centimeters of clearance. Once the pieces are lowered into the tunnel, they are slid together. The collider is like a Christmas toy that comes with the warning "Some assembly required."

Five miles away a different team is assembling an even larger detector standing five stories tall and containing eight toroidal magnets, each 80 feet long and 16 feet wide. Across the border, in France, scientists are testing hundreds of 50-foot-long superconducting magnets, devices so huge they must be moved with "Robotrucks" and yet contain components built to tolerances as tight as a few millionths of a meter. Deep underground, crews have already installed 250 of these magnets in the tunnel, where workmen zip along on bicycles or on electric carts that look like something out of a James Bond flick.

The tunnel was created for an earlier, less powerful particle accelerator, which was shut down in 2000. The older machine used smaller magnets that allowed ample room for maintenance workers to make repairs. The larger magnets in the new collider, along with their accompanying cryogenic system, will crowd the tunnel, making access more difficult. So while in the previous accelerator a single faulty magnet could be pulled out without much trouble, replacing one now may require removing dozens of others stacked between it and the nearest access point.

Once the magnets are installed and proton beams are zooming around the ring, physicists from around the globe will begin to gather data from collisions. Each second, 3,000 packets, each containing 10 trillion protons, will make 11,000 round-trips of the ring. Most protons pass through without colliding, but under optimal conditions up to 800 million collisions can occur in a single detector each second. Of these only a tiny percentage provide useful data--perhaps one in 10 trillion. A computer "grid" of thousands of small servers will churn through petabytes (quadrillions of characters) of data to find meaningful collisions. "It's like looking for a grain of gold on a beach," says Lucio Rossi, an Italian physicist who oversees the assembly and installation of magnets.

By measuring particles sprayed from collisions, physicists hope to get a glimpse of the universe as it existed just after the Big Bang and to figure out, among other things, why matter has mass. Key to that question is the search for a particle called the Higgs boson. Other accelerators, like the one at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois, have failed to find this elusive particle. The CERN supercollider will smash protons at energy levels seven times those at Fermilab and so might succeed where Fermilab has failed. The discovery of the boson just might persuade CERN's members that their contributions were not in vain. (The U.S., which has "observer" rather than "member" status, put up $580 million.)

Engineers have scheduled three days of downtime a month for routine maintenance. But glitches could take the system down for six weeks: three for the magnets to warm up and three to chill back down to operating temperature of 1.9 Kelvin. (That's minus 456 degrees Fahrenheit.) Such a shutdown would be especially devastating because physicists will use the collider only 140 days a year. (The machine draws as much power as a small city, so CERN will run it only in summer months, when electricity prices are half of what they are in winter.) As Martel puts it: "Four breakdowns in a year means no physics gets done."

Hoping to avoid such a calamity, Martel's group created the program to track virtually every piece of equipment used in the collider, from the wires and connectors on superconducting magnets to the fittings on the cryogenic system. In all, 2,000 contractors in 80 countries are providing equipment. If a component gets recalled, the engineers can spot all the places where it has been installed.

This program is based on the same commercial software CERN uses to schedule repairs for broken windows and burnt-out lightbulbs. It is made by a U.S. company called Datastream. When Martel proposed using Datastream in 2000, he encountered resistance from fiefdoms--cryogenics, magnets--which in the past had controlled their own data and weren't crazy about sharing. "It was a tough fight. You would not believe it," says Martel, a native of Portugal. After a year of haggling, in 2001 CERN's brass approved Martel's proposal. But then Martel ran into resistance from external suppliers who viewed the software as a headache. Some even sought to be paid extra since using software hadn't been specified in their contracts. (This is Europe, after all.) In the end the contractors fell in line, in some cases after renegotiating contracts.

The other challenge was writing 185,000 lines of code. Martel and two other engineers first customized the Datastream program, then added features to tie it into an Oracle (nasdaq: ORCL - news - people ) database and a document management application. Then they made it possible for people to enter information using only a Web browser. The program also helps physicists position the magnets. No two are identical; each has tiny irregularities in its magnetic field. The trick is to optimize performance by finding magnets whose irregularities cancel one another out and placing them next to one another. "It's like a big jigsaw puzzle," Martel says.

Martel's software also helped fix a potentially disastrous problem. In December 2004 engineers discovered a design flaw in the sliding table of the cryogenic system. The software identified every spot where the flawed part had been installed or was due to be installed, so assembly could be halted while the table was redesigned and new units were constructed. CERN officials say they have recovered most of the six months lost to the delay and expect to get the collider running on schedule next year. Then all they have to do is figure out how the universe began. Piece of cake.

Anyhow, if you get a chance to look at the magazine at a newstand there are some nice full page pictures.

-Mike

Post Script: I am aware most of this is already known to us, but i enjoyed reading it none the less; maybe someone else will.

blog pictures

blog pictures

|

![View the profile of [B^S] Molzahn Profile](https://lhcathome.cern.ch/lhcathome/img/head_20.png) [B^S] Molzahn

[B^S] Molzahn

![View the profile of [B^S] Molzahn Profile](https://lhcathome.cern.ch/lhcathome/img/head_20.png) [B^S] Molzahn

[B^S] Molzahn